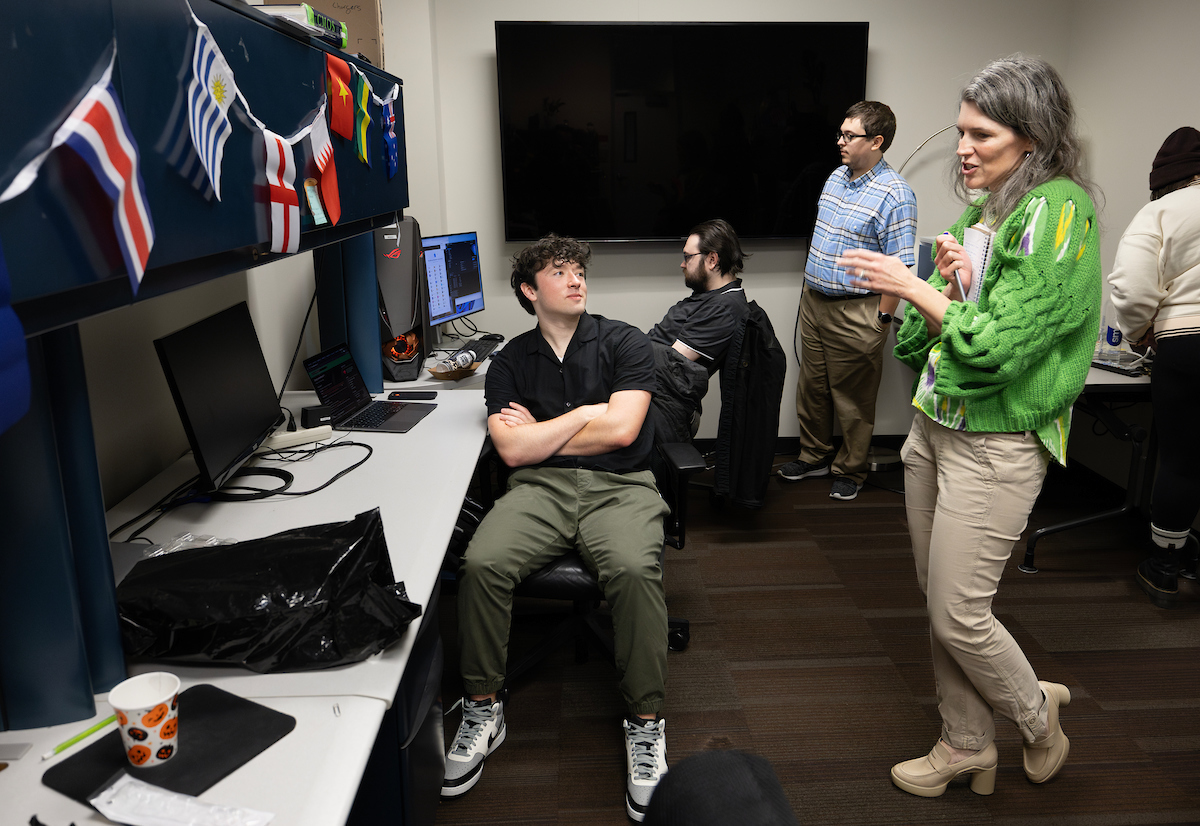

Mark Hasebroock spoke about his career and the lessons he’s learned along the way Thursday at Cornstalks. Photo by Danny Schreiber.

“I think I’ve actually learned more from my mistakes,” Mark Hasebroock says, “than I have from my successes.”

It’s a common refrain echoed by many who have been through the entrepreneurial wringer. But what’s uncommon about Hasebroock is the wide array of people, places and opportunities that have provided the learning experiences.

BECOME A SPONSOR

Join us in championing the narrative of success, resilience, and ingenuity that defines Nebraska’s startup community. Learn more »

Today, Hasebroock runs Dundee Venture Capital and is vice chairman of Hayneedle, which he helped found. But, as Hasebroock discussed Thursday at Cornstalks, he has worn many other hats. He’s worked in commercial banking, as a popcorn franchisee, in investment banking and in ecommerce. Through those experiences, Hasebroock has accumulated a catalogue of stories that are quite colorful — some in a very literal sense … like that time in college that his moccasin business backfired when the colored moccasins he sold stained customers’ feet.

“By learning from some of these mistakes, I was able to take some of these tools, pick myself up and start something new,” Hasebroock says. “I reflect back on the last 25-30 years, and it was obvious to me really where all these things came from.” On Thursday, Hasebroock shared some of the more lasting lessons he has learned by making occasional missteps along the way.

Moccasins and customer service

Hasebroock’s first entrepreneurial venture came when he was a student at the University of Nebraska and teamed up with a few friends to sell dyed moccasins. It seemed like a great way to help foot the bill for a spring break trip to South Padre. Until customers complained of the dye coming off the mocassins and staining their feet. “Every one of them had purple, green, yellow, red feet stained permanently from the moccasins,” Hasebroock said. “Everybody was upset.”

Hasebroock and his friends had to refund the customers’ money and buy new moccasins. But they learned some lessons in the process: first, know your suppliers; second, make customer service a top priority. “We figured out a way to do it,” Hasebroock said. “But, you know, it was a tough lesson.”

Banking and entrepreneurial aspirations

A stint in the management training program at First National Bank was extremely educational for Hasebroock, but it was also a tad frustrating. Time and again, Hasebroock came across entrepreneurs looking for loans for business ideas that intrigued him but didn’t fit the profile of people to whom the bank gave money. Eventually, he accepted that he’d have to look elsewhere to scratch his entrepreneurial itch.

“I started to realize ‘I don’t like this,’ because they teach you to say no, and I wanted to say yes,” Hasebroock recalled. “I was going to loan committee and saying, ‘I like this guy. He’s got a cool business. We should loan money to him.”

The response? “Mark, we don’t loan money to startups.”

Popcorn and acquisitions

Hasebroock became a franchisee with Vic’s Corn Popper despite limited knowledge of the business, and eventually he found himself wholesaling to grocers. “I’m literally making popcorn every morning at 5 in the morning,” Hasebroock said, “packing it, dealing with customers, setting up stores, payroll, you name it.

“It’s a tough, tough business,” he continued. “I knew nothing about it.”

Hasebroock took his lumps as he learned the wholesaling business but eventually started selling private-label popcorn, which helped the business take off. That attracted the attention of Scoular Grain, which purchased the company and in the process educated Hasebroock on acquisitions. “It was interesting for me,” he said, “because I got to see how a deal works – the negotiations, the structure, the closing, then the integration.”

“I learned companies from the inside out, not just as a banker but really an analytical perspective of, ‘What do they need, what drives them?’ And up above the trees, it was the people – just a common theme of really solid people.”

Private equity and people

After the Vic’s Corn Popper acquisition, Hasebroock’s interest in the business waned, and he decided to try his hand at investment banking. Omaha’s McCarthy Capital wasn’t hiring, so he offered to work there for free for six weeks. He wound up staying for 12 years. There, Hasebroock met Mike McCarthy, who he called “my supreme, No. 1 mentor in my life.”

The high-stakes nature of the work was taxing at times, Hasebroock said, because “if you sell a company, you get paid.” But through that process Hasebroock gained valuable insight on the best criteria for judging companies.

“It was a lot of both stress and excitement, and I found I kind of thrived on that” he said. “I learned companies from the inside out, not just as a banker but really an analytical perspective of, ‘What do they need, what drives them?’ And up above the trees, it was the people – just a common theme of really solid people.”

Hasebroock founded Hayneedle along with (from left) Julie Mahloch and Doug Nielsen. Screenshot from hayneedle.com.

Gift certificates, control and cash flow

In the late ’90s, Hasebroock met Doug Nielsen, who was looking for funding for his idea of an online gift certificate sales company. Nielsen and Hasebroock clicked immediately, and GiftPoint.com — it would later morph into GiftCertificates.com — was born.

But almost as quickly as Hasebroock, Nielsen and Julie Mahloch, Nielsen’s sister and a third co-founder, got the company off the ground, they saw themselves losing control. In search of funding to help scale, the co-founders took on too much VC funding, eventually diluting their stake in the company from 100 percent to less than one.

The company had a market valuation of $400 million and was set to go public, but as Hasebroock tells it, that plan, “vaporized, in a period of about 10 days.” Disenchanted with what their company had become, the co-founders decided to part ways and join forces on a different project sometime down the road. Then, they vowed, they’d avoid the missteps they had made the first time around. “We said … if we ever do something again,” Hasebroock recalled, “we’re not gonna lose control, it’s gonna cash flow itself and, by god, it’s gotta be fun.”

Hammocks and minding the metrics

That fun presented itself a matter of mere hours after Hasebroock, Mahloch and Nielsen parted ways. On Hasebroock’s last day at GiftCertificates.com, he fielded a call from a man in rural Washington who ran a business called Hammocks.com and wanted to become affiliated with GiftCertificates.com.

That certainly fit the “fun” description in Hasebroock’s mind, and in no time he, Nielsen and Maloch had reunited and purchased the business. That was the genesis of what became Hayneedle.

The lessons learned in the process of growing a business from a small hammock seller to what Hayneedle is today — an online retailer that has 265 stores, 300 employees and is projected to exceed $300 million in revenue this year — could populate a post of their own. But one lesson that stood out was the importance of removing emotion from business decisions and letting cold, hard metrics guide choices. As Hayneedle grew and diversified, it used “22 factors” to determine if a new type of product was a good fit to include under its umbrella of offerings.

“We established this discipline … we got a way to measure whether it works or not,” Hasebroock said. “And, believe it or not, we still do to this day.”

“I’ve always wanted to start my own little fund to help entrepreneurs avoid all the mines that I stepped on.”

“Venture capital” and harnessing life lessons

Now with Dundee, where he classifies himself as “not really an angel investor, not really a VC,” Hasebroock hopes to use the knowledge he’s accumulated through the years to help clear the way for new startups to build their own success stories. “I’ve always wanted to start my own little fund,” he said, “to help entrepreneurs avoid all the mines that I stepped on.”

Dundee has invested in Tripleseat, Graphicly and MindMixer, and Hasebroock hopes someday to see a landscape populated by successful companies seeded by his operation.

“We just kind of take the stuff we’ve learned over the last 25 years, and we try to apply it to some of these startups,” Hasebroock said. “And I hope, the aim is, that 10 years from now we create a lot of good companies here in Omaha and this region that are successful a lot faster than, you know, maybe I was able to do over 25 years.

“It just is so empowering to me to be involved in stuff like that. It’s very exciting.”