With college and professional sports up in the air due to coronavirus, athletes have more time on their hands than usual. Many are leveraging the downtime to connect with fans over social media: posting workouts, hosting livestreams, even setting up home podcast studios in the name of content creation.

While some might argue an athlete’s time would be better spent training, the decision to create digital content can be a strategic investment in one’s future. And a Nebraska-born company helps ensure that investment pays off—for the athlete, their fans, and the brands that want to connect.

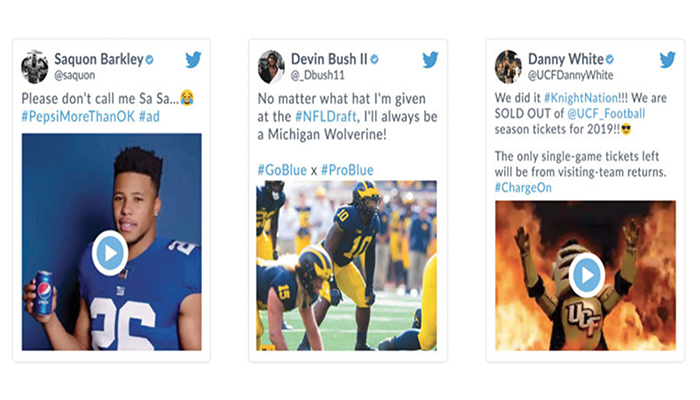

Opendorse is an athlete marketing agency co-founded by former Huskers and Hurrdat co-founders Adi Kunalic and Blake Lawrence with offices in Lincoln and New York. Using the platform, athletes can make money by approving social media content from sponsoring brands and posting it to their followers. The company was born from a desire to capitalize on the influence that athlete marketing can have on audience interaction, game attendance, merchandise sales, corporate partnerships, recruitment and viewership.

“We realized that there was a big problem that our technology [developed at Kunalic’s previous venture, the social media marketing agency Hurrdat] was solving: making it easier for athletes to streamline the way that they share content and connect with their fans,” Kunalic said.

The current moment is ripe for athletes and brands to connect with fans who worry their favorite sport might not happen next season, Kunalic said. Consequently, those fans could be tuning in to more sports-related content than usual, such as the 2020 MLB draft coming up in June. Releasing creative content that dovetails with such major league events could help athletes stay in consumers’ minds.

“From a share-of-voice standpoint, you have no other distractions,” Kunalic said. “It could be a cool way to test the waters and do some fun stuff.”

A Thriving Social Media Following Is Worth Big Money to Brands and Athletes

A bigger social media presence can translate to increased ticket sales, fan engagement, and business and endorsement opportunities, said Tony Veland, Director of Community Engagement for the AIM Institute, himself a former Husker and Defensive Back for the Denver Broncos and Carolina Panthers.

Veland cited the example of former University of Central Florida kicker Donald De La Haye. In 2017, De La Haye gave up his scholarship and NCAA eligibility to run his YouTube business, where he publishes vlogs about his life journey, puts on sports-related skits and demonstrates his kicking prowess.

“Social media was nonexistent in my day, so there really was no way for the athlete to market themselves to the masses, other than to perform at a high enough level where media outlets sought you out,” Veland said.

Social media effectively overcomes previous barriers to self-promotion, he added. Where athletes once suffered from lack of access to technology and distance from fans, they can now build their audience directly from their phones. And they can make money both from the content creation itself—once a creator hits 1,000 subscribers on YouTube, for instance, Google starts sending them a paycheck—and from the brands who’ll pay to reach an athlete’s followers.

The democratization of tech, and the attendant ability to leverage a digital presence into (eventual) economic opportunity, is especially significant for college athletes. A 2013 study found that in the Football Bowl Subdivision over 85 percent of student athletes on so-called full-ride scholarships live below the federal poverty line—despite their essential role in a multibillion dollar industry (“The Price of Poverty in Big Time College Sport”). Now that the NCAA’s Board of Governors has recommended college athletes should be able to profit from their likeness, enterprising student athletes will likely start pushing out content to build their social media followings and lure in sponsoring brands.

Opendorse recently calculated the potential per-post value of several college athletes based on their respective sports, audience sizes, engagement rates and additional proprietary data points. For instance, Paige Bueckers, who is committed to play point guard for the UConn women’s basketball team in 2020 and has over 518,000 followers on Twitter and Instagram, is potentially worth $20,962 per post. Meanwhile, Mikayla Colohan, a BYU women’s soccer midfielder with 2,624 followers, has a per-post value of $22.

Building a Social Media Following Builds Employable Skills

But gaining experience with content creation and production could be helpful for athletes at any stage in their careers, expanding their future employment and business prospects. Very few athletes can sustain a long, remunerative professional career. potentially helping them launch their own firms or land a job at an agency when they leave the game.

Plus, the constant immersion in technology required of an effective content creator might also influence some athletes to develop harder technical skills, like coding or UX design. Tech jobs pay well and are a likelier bet than a professional sports career, where the chances for long-term success are notoriously slim.

Veland, who after leaving the NFL embarked on a thriving career in the financial and technology sectors, encourages athletes to use the COVID downtime not only to study their sport, but to learn a new professional skill or two that could positively impact their future.

“Things such as learning how to network can benefit athletes in any walk of life,” Veland said.