Monolith, an innovative clean technology company, is expanding its footprint in Nebraska with the opening of its new global headquarters in Lincoln. Company officials say the move was spurred by Monolith’s commitment to sustainable practices and the chance to boost the local economy.

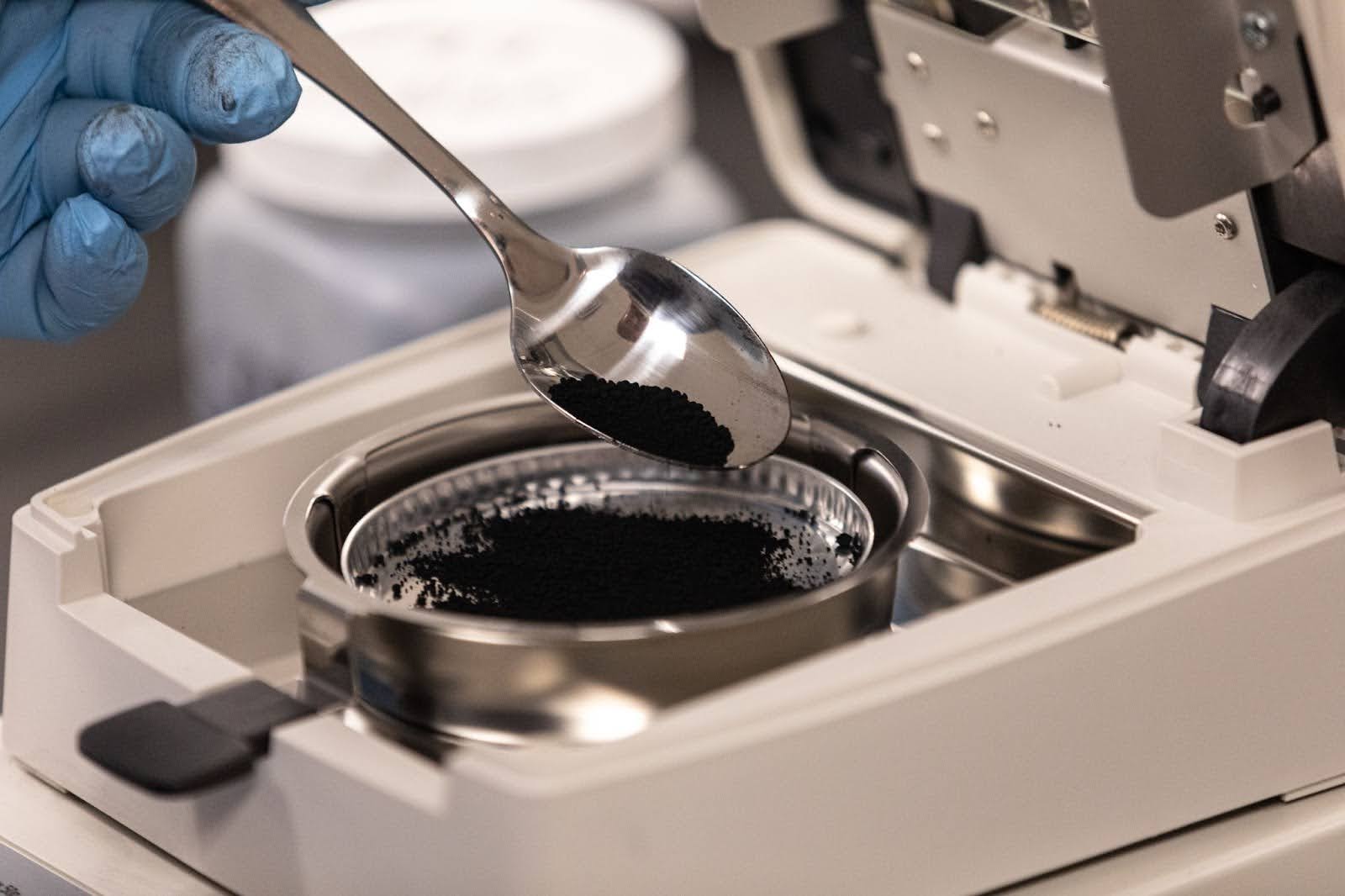

When Omaha-raised Dan Levy, now director of corporate communications, first started at Monolith, colleagues explained carbon black to him. During the initial explanation of why carbon black was key to making everyday products more sustainable, Levy realized the wide range of things it touches.

“I went home that day and I looked around the house and I thought oh my god this carbon black has been all around me forever, and I’ve never been aware of it,” Levy said. “Carbon black is a little bit like gravity. It’s all around you, but you don’t notice it.”

Monolith was founded by Robert Hanson and Pete Johnson in 2012, in Redwood City, California. Both of the founders wanted to create an organization that aligned with their vision of a high-energy, low-emission future. They believed innovation was key to solving CO2 emissions issues, rather than simply reducing car use or cutting back on activities, according to Levy.

Hanson and Johnson encountered methane pyrolysis technology—also referred to as methane cracking or methane splitting. Initially developed 40 years ago by Norwegian engineering firm Kvaerner, the process converts natural gas into clean hydrogen and carbon black. The falling price of methane made this technology economically viable. They realized that carbon black, a critical material in products like tires, could be produced sustainably through this method.

Carbon black is essential for strengthening tires, comprising 20-30 percent of a tire’s material. It is also used in various other products like coatings, seals and plastics. Seeing its potential, Hanson and Johnson set up a demonstration plant in Redwood City, California, from 2013 to 2015. It was the first new carbon black plant built in the U.S. in 50 years, Levy explained.

Monolith began producing carbon black and reached out to tire companies for feedback. The positive response led to plans for expansion, Levy said. In 2016 Monolith announced its move to Nebraska. Construction began on a commercial-scale unit called “Olive Creek 1” in Hallam, Nebraska. By 2020, the facility was operational.

Olive Creek 1 established Monolith as the world’s only commercially operational pyrolysis facility, right in Nebraska.

Now, the new Lincoln global headquarters at 600 P Street in the Haymarket District joins a rubber laboratory on West L Street and a 25,000-square-foot warehouse in South Lincoln, as well as the announcement of Olive Creek 2 receiving a conditional approval for a $1 billion U.S. Department of Energy loan.

“Moving the headquarters here was always part of the plan from back when we announced [Olive Creek 1] in 2016,” Levy said.

But the question remains: Why Nebraska?

Why Nebraska?

“We visited sites in Texas and Louisiana. We visited sites in Washington State and Iowa. We even went to New York State, but ultimately we ended up here in the state of Nebraska…There were many reasons, but the number one reason of why we ended up here is because of the people,” CEO and Co-founder Hanson said at the ribbon cutting ceremony for the new global headquarters.

Levy said Nebraska stood out for several other reasons, as well.

The availability of land was a factor. However, the local workforce was exceptional, meeting their expectations and aiding the transition from a demonstration facility to a commercial scale.

Additionally, Nebraska’s natural gas were crucial for their methane pyrolysis process, which requires intense heat without combustion in order to avoid CO2 emissions. The central location of Nebraska in the United States provided efficient distribution of their products in all directions.

Lincoln Partnership for Economic Development (LPED) worked with Monolith on choosing the Hallam site in 2015.

Economic boost

According to Dr. Eric Thompson, director of University of Nebraska-Lincoln Bureau of Business Research, Monolith has created 159 Nebraska jobs both directly and indirectly, $20.2 million in labor income and $46 million in annual economic impact since the opening of Olive Creek 1.

Monolith’s global headquarters now being located in Lincoln is significant to the city’s economy, LPED’s Vice President of Economic Development Luke Peltz said. “It brings several benefits such as job creation, increased tax revenue and enhanced local business activity.”

With the expansion of Olive Creek 2 in Hallem, they will build 12 more units—Olive Creek 1, is just one unit. It will produce more carbon black and use their clean hydrogen to produce ammonia for fertilizer.

The expansion is expected to create high-paying, advanced manufacturing jobs, Levy said. Their website says Olive Creek 2 will create 700 direct and indirect jobs.

“Beyond the financial investment, Olive Creek 2 will bring new employees to the Lincoln community resulting in an increase in economic activity,” Peltz said in an email.

Monolith recently started working with Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company to create a tire with their sustainability made carbon black for the Tesla Model 3, Levy said. The first tire to hit the market that is made with Monolith carbon black.

Monolith has also partnered with a company in March that has not been released yet. Monolith’s Chief Development Officer Amy Ostermeyer said with this new partnership there will be millions of tires on the road this time next year with its product made right here in Nebraska.

Methane pyrolysis process and environmental impacts

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, traditional carbon black is produced by reacting a hydrocarbon fuel (such as oil or gas) with a limited supply of combustion air at high temperatures ranging from 2400 F to 2800 F. This reaction results in the formation of extremely fine black particles, measuring 10 to 500 nanometers in diameter—carbon black.

In the United States, the oil furnace process and the thermal process are the main methods used to create carbon black. The oil furnace process dominates, accounting for about 90 percent of production, while the thermal process accounts for about 10 percent.

Over 15 million metric tons of carbon black produced annually emit carbon dioxide in the range of 29–79 million metric tons each year. Monolith’s innovative process produces even lower emissions.

Monolith uses a methane pyrolysis process. This involves breaking down methane (CH₄) into its constituent elements: carbon (C) and hydrogen (H₂), without burning the methane. The process is driven by renewable electricity, making it a low-emission alternative to conventional carbon black production.

The primary difference between traditional processes for producing carbon black and the methane pyrolysis process is in the feedstock, reaction conditions and byproducts.

Feedstock: Traditional processes use aromatic hydrocarbons or natural gas. Methane pyrolysis uses methane exclusively.

Reaction Type: Traditional processes involve combustion or thermal cracking. Methane pyrolysis involves non-combustive thermal decomposition. Methane is thermally decomposed into solid carbon and hydrogen at high temperatures without combustion

Byproducts and Emissions: Traditional processes can produce various hydrocarbon byproducts and involve handling exhaust gasses. Methane pyrolysis primarily produces hydrogen and solid carbon, with little to no CO2 emissions.

“The process of using natural gas instead of traditional fossil fuels to make carbon black reduces carbon emissions and the environmental impact. This commitment to sustainability aligns with trends toward green technologies and practices, further enhancing Lincoln as a forward-thinking city,” Peltz said.

A bright future in Nebraska

Monolith’s expansion in Nebraska marks a significant milestone in the company’s growth, creating environmental advantages and economic impacts for the state, Levy said.

Gov. Jim Pillien said at the ribbon cutting ceremony, “What I’m really excited about is the talking about what the future of Nebraska is. It’s about creating extraordinary great high-quality jobs.”

When Hanson came to America from Canada in 2006, he was chasing his own American Dream. He went to where he thought the center of innovation was, Silicon Valley in California.

But since, Hanson has changed his mind.

“This is the Silicon Valley of my dreams, and it can be anywhere. It is right here in Nebraska, where through that combination of engineering and manufacturing, we’re building one of the next great American companies.”