Hundreds of people from Nebraska’s corporate, startup, government and lobbyist worlds converged on the Marriott Omaha Downtown for the third annual Tech Nebraska Summit on Oct. 30.

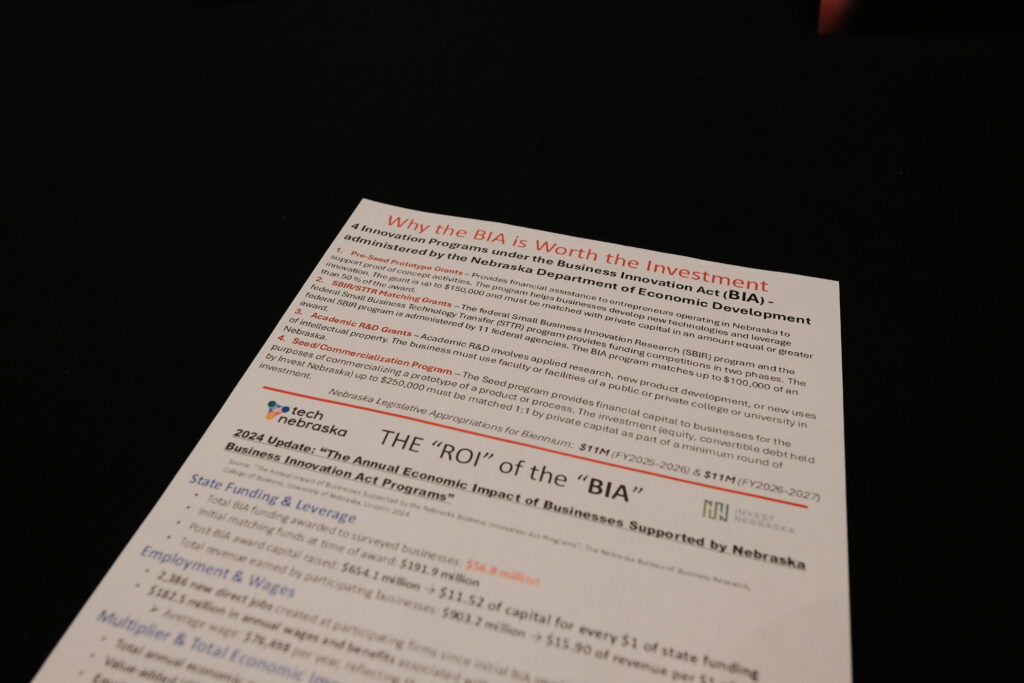

Center stage was a focus on restoring funding to Business Innovation Act programs, which are a cornerstone of the state’s startup ecosystem. Fliers about the importance of the BIA were on tables in the main convention hall, and the BIA regularly came up throughout the day.

The event was a kind of relaunch for Tech Nebraska under new Executive Director Emily Allen. The organization was founded in 2023 in partnership with the Nebraska Chamber of Commerce & Industry to be the member association and lobbying voice for the state’s tech industry.

“Three things we’re focused on with Tech Nebraska: Programming, so incredible events like today. Peer-to-peer interaction, so (chief information officers) and (chief technology officers) really getting connected with one another. And then policy,” Allen said in opening remarks.

“Tech Nebraska truly aims to be the definitive voice in tech policy for the state of Nebraska.”

Chris Dill, chief information officer at the Kiewit Corporation and the executive committee chair of Tech Nebraska, highlighted some of today’s policy priorities, including artificial intelligence and privacy regulations.

“Other states have started to entertain and or pass AI legislation,” Dill said, adding that it is “really important that Nebraska doesn’t do anything that limits our organization’s abilities to be competitive and creative.”

Dill called the Nebraska Department of Economic Development’s decision to pause new awards for BIA programs “a poor choice.”

“It needs to be rethought, and quickly. And I think Tech Nebraska is going to lend our voice to that effort in every way we can,” he said.

Panels on venture capital and startups point to a lack of corporate investment

Panelists in a breakout session on venture capital, titled “From Angels to Exit: Securing Funding at All Stages,” brought up an ongoing disconnect between Nebraska’s corporate behemoths and its startup ecosystem.

Panelists agreed that the most important thing Nebraska’s businesses can do for startups is to be a customer. But often, the corporate world isn’t interested in doing so — leaving founders to focus outside the state.

Take Workshop, the internal communications startup for enterprise. Early on, Workshop “had more success by reaching outside the state than inside, because a lot of the large corporations (were skeptical) — ‘Could the best solution really be down the street,’” said Charlie Cuddy, managing partner at Move Venture Capital.

A knock-on effect is taking the wealth Nebraska grows and sending it out of state. “There’s a ton of investors in South Dakota and Chicago that are getting access to phenomenal deals in Nebraska,” Cuddy said. “When those companies inevitably go and be successful, we’re going to send a ton of capital (to those places), just because people aren’t writing checks here.”

A subsequent panel, titled “Startups and Beyond: Building, Scaling and Staying in Nebraska,” had sharper criticism. The corporate reticence to support startups leads to many shutting down, panelists said, actively hampering Nebraska’s innovation.

“You want to talk about brain drain,” said Kellee Mikuls, executive director of Ignite Nebraska, a nonprofit that upskills talent into tech jobs. Mikuls was the founder of Swishboom, a child care startup that closed in part because it struggled to get corporate clients.

“Companies in this town have the capital to be able to step up and be the first customer, and they’re going to lose out on great startups, great ideas, and they’re going to close — like mine, or others that won’t even start because they don’t have those types of support,” Mikuls said.

Panelists reflected on the importance of Business Innovation Act programs like the prototype grant. The matching grant increased the impact of investments from venture capitalists like Nebraska Angels and Invest Nebraska.

The BIA’s support was also key because it gave founders the opportunity to learn and grow as they scaled their startup. Those skills, whether or not the startup shut down, continue to be essential to Nebraska’s workforce development.

“Now, as the executive director of (Ignite Nebraska), I have an email that is sitting in my inbox right now — Department of Health and Human Services said we will commit to hiring 500 of Ignite Nebraska participants in our agency, and the state of Nebraska is going to give us $4 million to grow across the state,” Mikuls said.

She attributed the contract success to the Ignite Nebraska team.

“But if I hadn’t learned what I learned by scaling and failing a business that was given that prototype grant — (which) gave me that opportunity — I wouldn’t be in this position to be able to grow this nonprofit that has so much economic impact.”

AI and energy take top spots for policy

A panel discussion about the policy priorities for Nebraska’s tech industry started by making clear why businesses need to keep an eye on the state’s decision making.

“The phrase has been said, ‘Either get into politics or get out of business,’” said Todd Bingham, CEO of the Nebraska Chamber.

Today, every company is fundamentally a tech company, Bingham said, making it even more important for Nebraska’s corporate world to engage with Tech Nebraska. With technology’s rapid evolution, there’s now a more intense focus on regulation.

“Five to seven years ago, it was rare that we had much tech legislation. Now it’s rare that we don’t,” said Dan Harbeke, the regional head of public policy and external affairs for Google.

AI is the latest target for policymakers. Jen Creager, the senior vice president of public policy at the Greater Omaha Chamber, referenced LB 642. The bill, introduced last legislative session by State Sen. Eliot Bostar, aims to protect consumers from algorithmic discrimination.

Creager said the bill had elements the business community liked and others that it took issue with. “Technology is so pervasive in every company that we think that it’s kind of hard to apply a one size fits all, very structured regulatory system in the state of Nebraska,” she said.

Google’s Harbeke said the state needs to find the right balance of necessary regulation while not impeding business. “AI is too important not to regulate — but it’s too important not to regulate well,” he said.

Another area of concern is the state’s energy infrastructure. Data centers, and the increased electricity demand from industries like manufacturing, are pushing the state’s power grid to its limit. Business leaders and policymakers worry the lack of power capacity is stunting economic development in Nebraska.

But that’s also an opportunity for the business world, said Rochelle Mallett, the executive vice president of state government affairs at lobbying firm HB Strategies. “If we are not a part of the solution, if we don’t get creative about how to solve this, they’re going to solution it for us — and we’re not going to like that,” she said.

There’s plenty to worry about when it comes to economic development in Nebraska, Creager said. She described a “death by a thousand cuts” that state efforts are facing, including the damage done by pausing Business Innovation Act programs.

It’s difficult “when programs exist and then all of a sudden they don’t exist,” Creager said. “All of a sudden the government will say, ‘Well, we’re not going to accept applications, or we’re going to take that money back.’ Even though the legislature acted … That’s a huge problem for anybody who wants to rely on the state as a partner in your efforts: That you can’t believe what they’re going to say, what they’re going to do.”

Lev Gringauz is a Report for America corps member who writes about corporate innovation and workforce development for Silicon Prairie News.